A New Library (1913-Great Depression)

The Vermont Square Branch Library officially opened at 6:00 PM on March 1, 1913 with a private black-tie event in the library’s auditorium (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 1; Los Angeles Public Library, 1988, p. 2). Hundreds of important people showed up for the ceremony. Speeches were given by the Henry Newmark, President of the Los Angeles Library Board of Directors; Everett R. Perry, the City Librarian at the time; and H.H. McCallum, the president of the Vermont Square Improvement Association. The rest of the Library Board members as well as the library’s new staff members were present to celebrate the opening of the new library (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 1.).

On Monday March 17, 1913, at 9 AM, the library opened up for public use. The community seemed to enjoy the new library. By the end of the month, over 1,000 people were registered library-card holders. Also, the library’s collection had totaled 2,285 and its circulation was 3,769. At the end of the fiscal year, in July, the library’s book collection increased to 4,008, circulation reached nearly 6,000, and over 2,000 people were library-card holders. Hence, the new library was a success among the community’s masses and became the most popular library in the city (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 1).

During the library’s first year, there were only two staff members working: Miss Brittan and her assistant, Veva Hart (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 1). According to a report, in the early 1900s, an average head librarian’s salary was $150/month; hence, this is what Brittan may have been earning (Hansen et al., 1997, p. 341). The library was opened weekdays and Saturdays from 9 AM to 9 PM, and Sundays from 2 PM to 6 PM. By 1915, there were library pages and aides working in the library; also, the first children’s librarian, Clara E. Perdum, was added to the staff (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 1). In 1916, Brittan left the library and was succeeded by Elizabeth C. Riddell, who took over as head librarian. In 1919, Riddell left the library and Veva Hart took over as head. In 1920, she transferred to the Lincoln Heights Branch and was succeeded by Emilie Jackson. At the end of 1920, Jackson transferred to a new library and Jessie Cavanagh was appointed as head librarian. In July of 1929, she transferred to the Felipe de Neve Branch and was replaced by Helen Spotts, Vermont Square’s most famous librarian to date (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 1.).

In the late 1920s and 1930s, there were many staff changes that occurred in the library. Many library assistants and senior librarians were coming and going. Staff members such as Lulah Meyers Lloyd, Oak Amidon, and Bess Markson were taking positions as head librarians in other branches. Others were retiring or died of old age, such as Mary Gertrude Hart. However, this frequent change of staff was not detrimental, but helped the library rise to prominence (due to the well-known people who were being hired) (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 2).

In the meanwhile, the Vermont Square Branch was a major community center. The Vermont Square Improvement Association took pride in the library and held meetings in its auditorium. Dr. Dennett, a pastor at the local church, actively worked with the library to provide services for youths. The library began adding new services and machinery, such as a motion picture projector, to draw in more children and adults. Hence, clubs and other programs were started, in which those in the community actively participated in (more information will later be provided) (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, pp. 2-3).

During World War I, the Vermont Square Library was the hub of patriotic activity. The Red Cross organized its drives there and held meetings in the auditorium. The branch organized book drives for camp libraries, receptions for local-area drafted soldiers, and food drives. Groups such as the Women’s Council for Defense, the Home Guards, and the War Saving Stamps Societies used the library’s auditorium to hold their meetings, organize demonstrations, and conduct relief work. Other groups were still using the auditorium, however, to hold their meetings, such as the Boy Scouts and the Southwest Realty Board. Also, neither war nor the Great Depression prevented the library’s circulation from descending; in fact, circulation reached an all-time high during that entire era, reaching well over 400,000 in the early 1930s (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 3). Hence, it is evident that the library continued to be a popular community center even during troubled times.

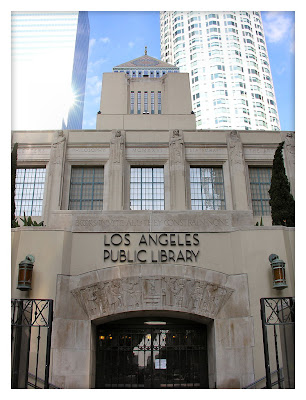

-Exterior shot of the Vermont Square Branch Library

In 1931, the library threw a party to celebrate its 18th anniversary. All members of the community were invited to attend. Alice Ames Winter, a librarian from Boston, was the speaker of the evening. In addition, Frances Harmon-Zahn, a member of the Library Board, and City Librarian Althea Warren also gave brief speeches. The celebration was a huge success and community members sent letters of appreciation to the library for it. Thus, the community continued to show its strong support towards the branch library during the Great Depression era (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, p. 6).

However, not all was well during that time. For instance, in March of 1933, an earthquake hit Southern California and the library got damaged; however, the following summer, it was repaired and the interior was redecorated (new light fixtures and paint) (Los Angeles Public Library, 1996, p. 2). Also, the library’s funds were reduced from $5,700 to $2,237. Were it not for their rental collection, the library may not have stayed afloat during the Depression. However, with the start of the 2nd World War encroaching, the hard times began to diminish and the library’s book fund mounted back to its near pre-depression level (Los Angeles Public Library, 1920, pp. 5-6; Los Angeles Public Library, 1949, p. 6).